Kedi

Most have experienced the mesmerising quality of cats and their unique personalities. In his first feature-length film, Turkish director Ceyda Torun has created an urban wildlife documentary that gives a snapshot of a city’s fascination with its homeless feline population.

Most have experienced the mesmerising quality of cats and their unique personalities. In his first feature-length film, Turkish director Ceyda Torun has created an urban wildlife documentary that gives a snapshot of a city’s fascination with its homeless feline population.

Kedi (Turkish for “cat”) is a charming film that traverses the urban landscape of Istanbul, telling stories of its large semi-domesticated cat population and the people who care for them. The film operates loosely as a social anthropology doco and a portrait of mankind’s relationship with their feline counterparts. One thing’s for sure, LOL cats this isn’t.

Much of the footage is taken from the cats’ eye view, with Torun’s camera getting down and dirty among the nooks and crannies of Istanbul’s back streets. Torun uses drones, radio control cars, and hand-held cameras to evoke a pseudo guerrilla style of film-making that gets right in amongst the cats’ lives. Despite the film’s lo-fi attitude, it delivers some stunning cinematography and if cats aren’t your bag then the film still offers a wonderful look at the colourful street-life of Istanbul.

Throughout, various cat “owners” pontificate philosophies and life lessons learnt from their moggies. One says “A cat meowing at your feet, looking up at you is life smiling at you.” It might be life smiling at you or just a hungry cat—either way, many cat owners will relate to the film’s sentiments.

At Kedi’s heart is a subtext that offers an insightful comparison with human homelessness. Many of the film’s stories operate as a parable of the less fortunate and should remind many of us that we are only an adverse turn from similar circumstances. As one “owner” ponders: “the troubles that street cats or other street animals face are not independent of the troubles that we all face.”

Despite this, Kedi remains a little too upbeat in its scope and seems to ignore the many realities of a city overrun (as some would consider) by cats. For some Kedi will be a fascinating look at a city’s homeless population, for others this will be a Gareth Morgan nightmare.

See my Witchdoctor reviews here.

I’m unapologetically lukewarm about the superhero genre having long suffered the much-maligned superhero fatigue.

I’m unapologetically lukewarm about the superhero genre having long suffered the much-maligned superhero fatigue.

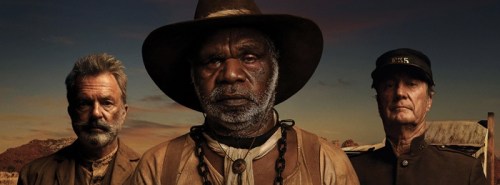

“What chance has this country got?” So asks Sam Neill in the Sweet Country’s final moments. Such is the film’s central theme as it examines Australia’s sordid racial past and brings its concerns into the present with a film that is as tragic as it is strikingly beautiful.

“What chance has this country got?” So asks Sam Neill in the Sweet Country’s final moments. Such is the film’s central theme as it examines Australia’s sordid racial past and brings its concerns into the present with a film that is as tragic as it is strikingly beautiful. Dominique Abel and Fiona Gordon team up once again, opening a kitbag of acting, writing and directing talents that can best be described as an “acquired taste”. Their films feel like an unwieldy blend of Mr Bean and Wes Anderson minus the comic timing or genius, and Lost in Paris is no different, with a gratuitously quirky style that renders it insufferably twee. Despite wanting to be, The Grand Budapest Hotel this is not.

Dominique Abel and Fiona Gordon team up once again, opening a kitbag of acting, writing and directing talents that can best be described as an “acquired taste”. Their films feel like an unwieldy blend of Mr Bean and Wes Anderson minus the comic timing or genius, and Lost in Paris is no different, with a gratuitously quirky style that renders it insufferably twee. Despite wanting to be, The Grand Budapest Hotel this is not. In a modern-day take on Beatrix Potter’s beloved leporine tale of the same name, director Will Gluck has drummed up a warren of talent that would be the envy of any studio. James Cordon, Domhnall Gleeson, Margot Robbie, Daisy Ridley and Elizabeth Debicki, among others, all chip in to flesh out this story about a cheeky (and very cute) anthropomorphised rabbit and his battle for a vegetable patch.

In a modern-day take on Beatrix Potter’s beloved leporine tale of the same name, director Will Gluck has drummed up a warren of talent that would be the envy of any studio. James Cordon, Domhnall Gleeson, Margot Robbie, Daisy Ridley and Elizabeth Debicki, among others, all chip in to flesh out this story about a cheeky (and very cute) anthropomorphised rabbit and his battle for a vegetable patch.