Lean on Pete

Acclaimed British writer/director Andrew Haigh has shifted focus from English domestic life in his much-lauded film 45 Years, to America’s north-west. His portrait of a rural America languishing in deep-seated economic woes isn’t a particularly flattering one, but it is a beautifully shot and incredibly powerful one.

Acclaimed British writer/director Andrew Haigh has shifted focus from English domestic life in his much-lauded film 45 Years, to America’s north-west. His portrait of a rural America languishing in deep-seated economic woes isn’t a particularly flattering one, but it is a beautifully shot and incredibly powerful one.

Adapted from Willy Vlautin’s book of the same name, Lean on Pete centres on a soft natured but emotionally resilient teen named Charley (Charlie Plummer). While his dad is holed up in hospital, he meets by chance a race-horse trainer (Steve Buscemi) who runs the lower-level race circuits in Oregon. Bonding with a flagging racehorse who seems destined for the glue factory, Charlie decides to steal the horse across state. But far from the sentimental boy-and-his-horse tale you might expect, this road-journey (of sorts) is a desperately human tale that is more concerned with a boy’s need for belonging.

The film’s haunting score and fawning cinematography swoon over the American landscape, providing Haigh’s screenplay ample space and time to soak in Charley’s milieu. This is a masterclass of contemplative cinema; a slow-burn that encourages a strong sense of connection with Charley’s plight. It is sublimely moving, occasionally heartbreaking, and always engaging.

Haigh appears to have an eye for acting talent and his gamble to hang the whole film on Charlie Plummer’s performance has paid off. Plummer (All the Money in the World) is an immense talent and repays Haigh’s trust by delivering the film its heart and soul. If you were mesmerised by New Zealand’s own Thomasin McKenzie’s nuanced and introspective performance in Leave No Trace, then you will find Plummer’s performance a perfect companion piece.

Working from his own screenplay, Haigh avoids cheap sentimentality and credits his audience with enough patience to dig beneath its gentle nature and root out meaning. And dig you should, because beneath the surface is a film that will pack an emotional gut punch.

See my reviews for the NZ Herald here and for Witchdoctor here.

In a cinematic version of hanging your Christmas decorations out too early, The Grinch begs the question of why we need a Christmas story in November, let alone one from the well rinsed Dr. Seuss pantheon. But here we have it.

In a cinematic version of hanging your Christmas decorations out too early, The Grinch begs the question of why we need a Christmas story in November, let alone one from the well rinsed Dr. Seuss pantheon. But here we have it. Scottish writer/director Kevin Macdonald is perhaps best known for his chilling account of Idi Amin in The Last King of Scotland.

Scottish writer/director Kevin Macdonald is perhaps best known for his chilling account of Idi Amin in The Last King of Scotland. Seven years ago Scottish director Lynne Ramsay ushered us, along with a very tired looking Tilda Swinton, into the disturbing world of Kevin. Among other themes, We Need to Talk About Kevin was a cold hard look at the warped mind of a killer. Ramsay’s damming statement on America’s weaponised culture was curiously (and perhaps more strikingly) made with the absence of guns. You Were Never Really Here is no different as it follows a “hired gun”, who plies his trade with a ball-peen hammer. Although one should know never to take a hammer to a gun fight, Joe who is played by a very beefy looking Joaquin Phoenix certainly knows how to swing one.

Seven years ago Scottish director Lynne Ramsay ushered us, along with a very tired looking Tilda Swinton, into the disturbing world of Kevin. Among other themes, We Need to Talk About Kevin was a cold hard look at the warped mind of a killer. Ramsay’s damming statement on America’s weaponised culture was curiously (and perhaps more strikingly) made with the absence of guns. You Were Never Really Here is no different as it follows a “hired gun”, who plies his trade with a ball-peen hammer. Although one should know never to take a hammer to a gun fight, Joe who is played by a very beefy looking Joaquin Phoenix certainly knows how to swing one. The antisocial hacker and ball-breaker Lisbeth Salander has finally made a return to the big screen in this adaptation of David Lagercrantz’s fourth book of the “Millenium” series. Departing from the brooding drama and gritty violence of Stieg Larsson’s first three stories, this tale instead heads down the more conventional Hollywood path.

The antisocial hacker and ball-breaker Lisbeth Salander has finally made a return to the big screen in this adaptation of David Lagercrantz’s fourth book of the “Millenium” series. Departing from the brooding drama and gritty violence of Stieg Larsson’s first three stories, this tale instead heads down the more conventional Hollywood path.

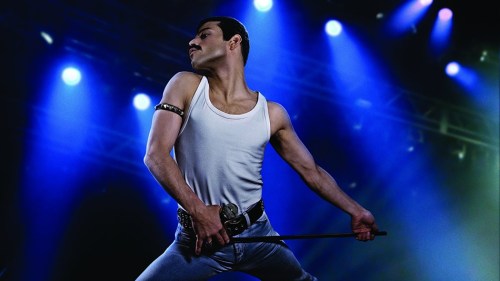

As a tousle-haired bedroom-poster-hanging teen of the eighties and nineties, the news of Freddie Mercury’s death came to me as quite a shock. Love him or not, there is no denying Queen had an omnipresent quality that seared their sound on the musical psyche of the masses. So, a film that explores this phenomenon was always going to be a very personal journey for many.

As a tousle-haired bedroom-poster-hanging teen of the eighties and nineties, the news of Freddie Mercury’s death came to me as quite a shock. Love him or not, there is no denying Queen had an omnipresent quality that seared their sound on the musical psyche of the masses. So, a film that explores this phenomenon was always going to be a very personal journey for many.