The Red Turtle

The Red Turtle has recently done the rounds of the film festival circuit, including our own New Zealand International Film Festival. A collaboration between Studio Ghibli and Oscar-winning Dutch born writer-director Michael Dudok de Wit (Father and Daughter) makes for an interesting fit. Dudok de Wit has applied his hand solely to short films to date, so it must have been an interesting turn of events that convinced him to work on a feature film with an animation studio from half a world away in distance and style. It took a decade to make, but make it they did, and the result is a genuine treat.

The Red Turtle has recently done the rounds of the film festival circuit, including our own New Zealand International Film Festival. A collaboration between Studio Ghibli and Oscar-winning Dutch born writer-director Michael Dudok de Wit (Father and Daughter) makes for an interesting fit. Dudok de Wit has applied his hand solely to short films to date, so it must have been an interesting turn of events that convinced him to work on a feature film with an animation studio from half a world away in distance and style. It took a decade to make, but make it they did, and the result is a genuine treat.

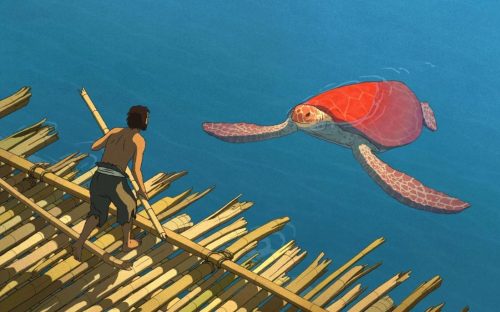

Entirely dialogue free, the film tells the simple story of a man (we never know his name) castaway on a deserted tropical island. His attempts to escape the island by a raft made of bamboo are repeatedly thwarted by the titular red turtle. Consequent to seeking his revenge upon the turtle, the film uncannily unfolds into a fantastical fable that explores themes of companionship, family, grief and man’s bond with nature … ultimately to its poignant and moving end.

The film’s art style is stunning and mimics the purity of its narrative, with clean lines and hyper-simplistic characters with simple dots for eyes, set against a painterly backdrop of the sea, sky, and island. There is a palpable splicing of Japanese and European art styles, almost as if Tintin walked onto the set of Ponyo.

A minimalist pace and lack of dialogue allows space to ponder what is presented before your senses rather than having to play catchup on any lengthy expositions. This is a refreshing approach and perhaps necessary of a film that implores us to look at nature through a simple lens. However, it is the provocative ambiguity that remains the film’s most attractive feature, and as such I was left basking in its tantalisingly elusive meaning for days after viewing — it’s almost as if the film is daring you to draw your own conclusion rather than present one for you.

Despite the Studio Ghibli pedigree, the slow pace means that audience patience, rather than subject matter, might make the film inaccessible to younger children. Although, I think perseverance in this instance would have its rewards, as this is a masterclass in sensory story telling. Look out for this film in the new year … it is definitely worth the wait.

Star rating: 4.5 stars.

Irish writer-director, John Carney, has had a string of hits and misses in his career. His surprise triumph, Once, beautifully expressed a delicate love story through song and picture and garnered critical success. However, Carney’s mojo quickly evaporated with his subsequent releases Zonad, and the recent foray into America with Begin Again, which was met with a tepid reception. His latest feature, Sing Street goes a long way to restoring his creditability as a director who can blend an authentic heart-felt story with music. Set in 1985 among the schooling milieu of a depressed Dublin, Sing Street ostensibly operates as an autobiography of Carney’s musical upbringing.

Irish writer-director, John Carney, has had a string of hits and misses in his career. His surprise triumph, Once, beautifully expressed a delicate love story through song and picture and garnered critical success. However, Carney’s mojo quickly evaporated with his subsequent releases Zonad, and the recent foray into America with Begin Again, which was met with a tepid reception. His latest feature, Sing Street goes a long way to restoring his creditability as a director who can blend an authentic heart-felt story with music. Set in 1985 among the schooling milieu of a depressed Dublin, Sing Street ostensibly operates as an autobiography of Carney’s musical upbringing.

It’s a question everyone asks – was the book better than the film? To me it seems a fruitless inquiry as they are such dramatically different mediums. In most cases the book wins out, simply because it allows the reader to imagine a picture, whereas the film has the onerous task of presenting that picture … which differs for everyone. In this instance, I saw The Girl on the Train having not read the book. So, I was charged with reviewing the film on its own terms rather than having to consider screenwriter Erin Cressida Wilson’s treatment of Paula Hawkins’ best-selling pot boiler.

It’s a question everyone asks – was the book better than the film? To me it seems a fruitless inquiry as they are such dramatically different mediums. In most cases the book wins out, simply because it allows the reader to imagine a picture, whereas the film has the onerous task of presenting that picture … which differs for everyone. In this instance, I saw The Girl on the Train having not read the book. So, I was charged with reviewing the film on its own terms rather than having to consider screenwriter Erin Cressida Wilson’s treatment of Paula Hawkins’ best-selling pot boiler. I regretfully admit that I have not yet seen the 1960 version of The Magnificent Seven (which was originally based on Akira Kurosawa’s 1954 Japanese classic, Seven Samurai). In fact, the whole western genre is a bit of a blind spot for me. However, the positive is that I can look at Antoine Fuqua’s (Training Day, The Equalizer) remake with fresh eyes rather than compare it to the original. Apparently I’m in good company – the film’s star, Denzel Washington, citing similar reasoning, didn’t see the original either.

I regretfully admit that I have not yet seen the 1960 version of The Magnificent Seven (which was originally based on Akira Kurosawa’s 1954 Japanese classic, Seven Samurai). In fact, the whole western genre is a bit of a blind spot for me. However, the positive is that I can look at Antoine Fuqua’s (Training Day, The Equalizer) remake with fresh eyes rather than compare it to the original. Apparently I’m in good company – the film’s star, Denzel Washington, citing similar reasoning, didn’t see the original either.

I am always on the look-out for a holiday film that draws out deeper reactions in my kids than a couple of cheap laughs. A few years ago, I took them to see Spike Jonze’s superb Where the Wild Things Are. Fair to say I was impressed by how complex themes were drawn out of Maurice Sendak’s seemingly innocuous 1973 book of the same name. It appeared to me that Pete’s Dragon might just have the same opportunity.

I am always on the look-out for a holiday film that draws out deeper reactions in my kids than a couple of cheap laughs. A few years ago, I took them to see Spike Jonze’s superb Where the Wild Things Are. Fair to say I was impressed by how complex themes were drawn out of Maurice Sendak’s seemingly innocuous 1973 book of the same name. It appeared to me that Pete’s Dragon might just have the same opportunity.