The Founder

It’s that time of the year where the heavily Oscar baited biopics tend to be released. So, it was with anticipation that I headed into the theatre to see the genre’s first cab off the rank.

It’s that time of the year where the heavily Oscar baited biopics tend to be released. So, it was with anticipation that I headed into the theatre to see the genre’s first cab off the rank.

Initially excited over reports that the Coen brothers were interested in directing The Founder, I was met with mild disappointment upon hearing that John Lee Hancock (The Blind Side), with his rather bland track record, had prevailed. Written by Robert D Siegel (The Wrestler), The Founder is based on the true story of McDonald’s founder Ray Kroc, and scopes the genesis of the well-known fast food giant.

The film’s title sardonically sums up its central thesis which explores to what extent Ray Kroc (Michael Keaton) was indeed the founder of McDonald’s. The story is bookended by Ray’s mantra on “persistence”, whereby he casts aside arguably more noble traits as mere folly in the face of good old fashioned persistence and determination; “Nothing in the world can take the place of persistence. Talent will not; nothing is more common that unsuccessful individuals with talent. Genius will not; unrewarded genius is almost a proverb. Education will not; the world is full of educated derelicts. Persistence and determination alone are omnipotent.”

Blinded by his tunnel visioned notion of persistence, Ray bulldozes his way towards success, casting aside the mild mannered Mac and Dick McDonald who first caught Ray’s eye with their original fast and efficient burger joint. Ray’s neglected wife, Ethel (Laura Dern), gets similar treatment and soon Ray, having collected a savvy bunch of advisers on the way, builds the fast food giant that we all know and have a love/hate relationship with.

On first impressions The Founder plays out a lot like David Fincher’s The Social Network, although its commentary on success and what people will do to obtain it, strikes with far less venom. Instead, it coasts along at a tame pace and the film occasionally risks stalling if not for the energetic performance by Michael Keaton who skilfully walks the tightrope of moral ignorance and myopic determination. Notable also is the cinematography which captures the era well without resorting to gimmickry. Ultimately, The Founder feels like an interesting yet somewhat uninspiring story, told through an entertaining yet somewhat conventional lens … like a tasty meal with little nutritional value.

Rating: 3 out of 5

You can see the published review here

At this years Venice Film Festival American director and fashion designer Tom Ford said of cinema— “You need to think about it. Things can be entertaining, but if you leave the theater and it doesn’t stay with you, doesn’t haunt you, doesn’t challenge you, then it’s not successful, for me. So I hope to make films that make one think.” Despite the recent buzz about Amy Adams, I found myself more excited to see her latest film, Nocturnal Animals, because I wanted to be “haunted” by Ford’s latest foray into cinema.

At this years Venice Film Festival American director and fashion designer Tom Ford said of cinema— “You need to think about it. Things can be entertaining, but if you leave the theater and it doesn’t stay with you, doesn’t haunt you, doesn’t challenge you, then it’s not successful, for me. So I hope to make films that make one think.” Despite the recent buzz about Amy Adams, I found myself more excited to see her latest film, Nocturnal Animals, because I wanted to be “haunted” by Ford’s latest foray into cinema. Starring Ben Affleck, Anna Kendrik, and J.K. Simmons, The Accountant is a bit Rain Man, a bit A Beautiful Mind, a hint of X-Men, and a whole heap James Bond … if Bond had autism (actually, it wouldn’t surprise me if ol’ Jimmy was on the spectrum). So, what’s not to like?

Starring Ben Affleck, Anna Kendrik, and J.K. Simmons, The Accountant is a bit Rain Man, a bit A Beautiful Mind, a hint of X-Men, and a whole heap James Bond … if Bond had autism (actually, it wouldn’t surprise me if ol’ Jimmy was on the spectrum). So, what’s not to like?

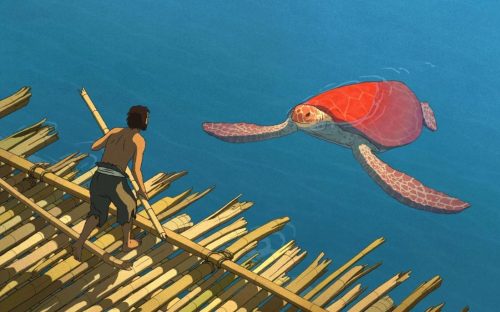

The Red Turtle has recently done the rounds of the film festival circuit, including our own New Zealand International Film Festival. A collaboration between Studio Ghibli and Oscar-winning Dutch born writer-director Michael Dudok de Wit (Father and Daughter) makes for an interesting fit. Dudok de Wit has applied his hand solely to short films to date, so it must have been an interesting turn of events that convinced him to work on a feature film with an animation studio from half a world away in distance and style. It took a decade to make, but make it they did, and the result is a genuine treat.

The Red Turtle has recently done the rounds of the film festival circuit, including our own New Zealand International Film Festival. A collaboration between Studio Ghibli and Oscar-winning Dutch born writer-director Michael Dudok de Wit (Father and Daughter) makes for an interesting fit. Dudok de Wit has applied his hand solely to short films to date, so it must have been an interesting turn of events that convinced him to work on a feature film with an animation studio from half a world away in distance and style. It took a decade to make, but make it they did, and the result is a genuine treat. Irish writer-director, John Carney, has had a string of hits and misses in his career. His surprise triumph, Once, beautifully expressed a delicate love story through song and picture and garnered critical success. However, Carney’s mojo quickly evaporated with his subsequent releases Zonad, and the recent foray into America with Begin Again, which was met with a tepid reception. His latest feature, Sing Street goes a long way to restoring his creditability as a director who can blend an authentic heart-felt story with music. Set in 1985 among the schooling milieu of a depressed Dublin, Sing Street ostensibly operates as an autobiography of Carney’s musical upbringing.

Irish writer-director, John Carney, has had a string of hits and misses in his career. His surprise triumph, Once, beautifully expressed a delicate love story through song and picture and garnered critical success. However, Carney’s mojo quickly evaporated with his subsequent releases Zonad, and the recent foray into America with Begin Again, which was met with a tepid reception. His latest feature, Sing Street goes a long way to restoring his creditability as a director who can blend an authentic heart-felt story with music. Set in 1985 among the schooling milieu of a depressed Dublin, Sing Street ostensibly operates as an autobiography of Carney’s musical upbringing.

It’s a question everyone asks – was the book better than the film? To me it seems a fruitless inquiry as they are such dramatically different mediums. In most cases the book wins out, simply because it allows the reader to imagine a picture, whereas the film has the onerous task of presenting that picture … which differs for everyone. In this instance, I saw The Girl on the Train having not read the book. So, I was charged with reviewing the film on its own terms rather than having to consider screenwriter Erin Cressida Wilson’s treatment of Paula Hawkins’ best-selling pot boiler.

It’s a question everyone asks – was the book better than the film? To me it seems a fruitless inquiry as they are such dramatically different mediums. In most cases the book wins out, simply because it allows the reader to imagine a picture, whereas the film has the onerous task of presenting that picture … which differs for everyone. In this instance, I saw The Girl on the Train having not read the book. So, I was charged with reviewing the film on its own terms rather than having to consider screenwriter Erin Cressida Wilson’s treatment of Paula Hawkins’ best-selling pot boiler. I regretfully admit that I have not yet seen the 1960 version of The Magnificent Seven (which was originally based on Akira Kurosawa’s 1954 Japanese classic, Seven Samurai). In fact, the whole western genre is a bit of a blind spot for me. However, the positive is that I can look at Antoine Fuqua’s (Training Day, The Equalizer) remake with fresh eyes rather than compare it to the original. Apparently I’m in good company – the film’s star, Denzel Washington, citing similar reasoning, didn’t see the original either.

I regretfully admit that I have not yet seen the 1960 version of The Magnificent Seven (which was originally based on Akira Kurosawa’s 1954 Japanese classic, Seven Samurai). In fact, the whole western genre is a bit of a blind spot for me. However, the positive is that I can look at Antoine Fuqua’s (Training Day, The Equalizer) remake with fresh eyes rather than compare it to the original. Apparently I’m in good company – the film’s star, Denzel Washington, citing similar reasoning, didn’t see the original either.