I have always been fascinated with colour how it is used in cinema. Specifically how the use of colour can be a powerful tool to convey “feelings” in film. The following is an excerpt from my thesis that discusses the relationship between cinema and colour. Here I define the term “cinematic complexion” and discuss how it facilitates “feeling” the film, often evoking new meanings and subtexts. In the coming days I will give brief accounts of how “cinematic complexion” reveals ways of viewing Aronofsky’s films that are often at odds with the narrative.

The Fountain (2006)

The Affective Image

The relationship between colour and mood appears to share a natural connection. Colour has the capacity to reach into my lived body and alter the way I feel. Notably, it can do this without having direct access to my physical body. It presents the same paradox as music, affecting my mood yet not having direct access to my somatic levers. This conundrum raises many questions, which I will explore in this chapter. Indeed, how can the colour of a film make me feel a certain way and alter my mood? Why does the changing complexion of Requiem for a Dream give my body a sense of morbid descent, and yet The Fountain makes me feel quite the opposite? Here, I refer to the term “complexion” as the film’s holistic colour — that is, the film’s dominant hues that coalesce over the length of the film to bring about its collective colour identity, or complexion.

It would seem logical to affirm that different colours encourage certain moods; a “vibrant” yellow encourages quite a different mood from a “gloomy” green. Here, I am mindful of my subjective use of descriptive terms. Such terms should not be dismissed due to their lack of objectivity. Instead, they provide an important descriptive tool that can be used to express an embodied experience. To describe colour using terms such as “vibrant” or “gloomy” is an appropriate way to apply Ihde’s second hermeneutic rule: “Describe, don’t explain.” As art theorist W.J.T. Mitchell suggests:

Figurative labels (“blue” moods and “warm” colours) apply as firmly and consistently as literal ones and have as much to do with actual experience. That images, pictures, space and visuality may only be figuratively conjured in a verbal discourse does not mean that the conjuring fails to occur or that the reader/listener “sees” nothing. That verbal discourse may only be figuratively or indirectly evoked in a picture does not mean that the evocation is impotent, that the viewer “hears” or “adds” nothing in the image (2009, p.119).

As with music, colour does not offer a definitive or tangible form of representation and objectification. Nevertheless, colour still has the power to affect our mood. The suggestion I make here is that colour in the cinematic model operates with a similar currency to that of the musical score, by providing emotionally appropriate objects. Kivy’s (2007) model of musical emotion can be applied to the use of colour; emotions are often stimulated by colour itself, suggesting that colour itself is the object. For example, we may be agitated by the sudden shift in a film’s complexion from an uplifting colour to an aggressive one, perhaps foreshadowing an unpleasant turn in the narrative. These emotions are stimulated by colour and are often narrative signposts or colourific cues that can sometimes take precedence over other narrative devices. In Black Swan colour is used to signpost a narrative turn during a night-club scene. Unbeknownst to Nina, her drink is drugged, leading her evening down an unscrupulous route. As she descends into her drug-addled haze, the film illustrates this by bathing the mise-en-scène in a deep red. This colour is used to visually emphasise a shift in narrative as well as illustrate the darker side of Nina. It also foreshadows the film’s climactic ending, where Nina’s darker side is fully realised through use of the same colour.

Furthermore, cinematic colour paradoxically operates beyond the visual realm. As an embodied spectator, my experience of colour informs my other senses. As Vivian Sobchack posits that “We do not experience any movie only with our eyes. We see and comprehend and feel films with our entire bodily being, informed by the full history and knowledge of our sensorium” (Sobchack, 2000).

Aronofsky’s first five feature length films utilise colour (or lack of, as is the case with Pi) to assist in the creation of mood. This is perhaps an unsurprising statement given that most directors have a colour scheme as part of their mise-en-scène. However, I want to stress the attention that Aronofsky gives to the complexion of each of his films. Moreover, I will investigate his intention to utilise this as a tool to alter the way the embodied spectator feels. I will avoid the question of how colour should be interpreted, thus avoiding psychoanalytical tropes, but rather ask: how does colour in his films make me feel and why? Like Jenefer Robinson’s audible odours (discussed in Chapter 2), colours operate in a similar fashion, cross-pollinating with other senses. A reddish hue might make me feel warm because of my memory of the colour’s natural occurrence within nature. Likewise, a bluish hue might make me feel cold because my natural experience of it is with cool items such as ice. Furthermore, these feelings are reinforced by signifying curators such as advertising, film, television, and other forms of media. That is, I see white and blue and feel cool not only because of my experience with nature but also because of its culturally appropriated representation in, say, a toothpaste advertisement. This cross-pollination of senses allows for the lived body experience of cinema. A question still remains: how does one feel colour? How does vision become a tactile experience? If, for example, I see a scene that is strongly tinted with orange, how does this imbue a feeling of warmth, or a blue scene imbue a feeling of cold? In order to answer this I will now return to Sobchack, whose phenomenological approach has been the philosophical backbone of this investigation.

In her article for Senses of Cinema (2000), Sobchack explores the relationship between the sensory experience of the spectator and the film.

We are in some carnal modality able to touch and be touched by the substance of images, to feel a visual atmosphere envelop us, to experience weight and suffocation and the need for air, to take flight in kinetic exhilaration and freedom even as we are relatively bound to our seats, to be knocked backwards by a sound, to sometimes even smell and taste the world we see on the screen (Sobchack, 2000).

Sobchack’s comments are not meant metaphorically. That is, our “need for air”, or to “smell and taste”, are not mere thoughts but tangible urges — physical responses to what has been presented before us. However, how can I smell, taste, or for that matter feel, when I am as Sobchack states, bound to my seat? When a film only presents itself within the sensory modes of sight and sound, how can this affect my other three senses? When I watch Tom (Hugh Jackman) eat the Tree of Life’s bark in The Fountain, I taste what I imagine the bark would taste like. When I watch Randy cut himself with a razor in The Wrestler, I feel what I imagine the pain would feel like. I hear the bark being cut and chewed by Tom, and I see Randy cut himself. Yet somehow my body responds to the sights and sounds presented with the senses of taste and touch.

Sobchack offers an explanation for my responses to this phenomenon. She argues that the spectator does not experience a film exclusively through the sensory modes of seeing and hearing, but instead with their entire “bodily being”, claiming that there is a dominant “cultural hegemony” of vision that prevents many spectators from fully experiencing film. She sees the sensory model as a series of interconnected modes rather than isolated senses, claiming that “vision is only one modality of [the] lived body’s access to the world” (2004, p.64).

Sobchack explains this interconnection of sensory modes through a concept she calls the “cinesthetic subject” — a contrivance born out of synaesthesia and coenaesthesia. Both of these conditions involve the interconnection of senses. Synaesthetes experience one sense as another, for example, sound is experienced as a colour, or a colour is experienced as a taste. Coenaesthesia refers to the spectator’s perception of their senses as a whole. Sobchack uses the example of the new born baby, who is only aware of his or her senses and has not yet been influenced by a cultural hegemony that privileges one sense over another.

Through these two conditions, Sobchack arrives at the “cinesthetic subject” — a constructed spectator whose senses inform each other, enabling and offering a reason why, as a spectator, one can touch, taste, and smell the cinematic image. Consequently, the borders between the senses are blurred as the cinesthetic subject experiences film through their lived body, not just through vision and hearing. Sobchack argues that the lived body coalesces the senses in a “cross-modal sensory exchange” (2004, p.69).

The cross-modal sensory exchange is processed by the spectator instinctively, through a form of “primary engagement” with the film. Sobchack explains that through this process, the lived body subverts the divide between the spectator off-screen and the character on-screen. That is, the spectator’s engagement with the film unsettles the established cinematic relationship between the subject (the spectator) and the object (the character). The lived body supplies a conduit for the cinematic experience as the spectator responds, thus blurring the boundary between spectator and character. The spectator feels what the character feels. For example, in Requiem for a Dream Harry lies on a prison floor suffering from a badly infected arm. His infected arm becomes a sensory experience that goes beyond mere sight and sound. My lived body becomes aware of Harry’s pain as I suddenly become conscious of myself rubbing my arm in response. Therefore, my skin is now not exclusively my own but has become part of an embodied experience, which is also Harry’s skin. In her phenomenological analysis of The Piano (1993), Sobchack experiences a similar affect, stating that “my skin is both mine and not my own” (2004, p.66). Thus, the spectator feels what the character feels through a reversibility of perception between the cinesthetic subject and, as Sobchack explains, the screen’s “figural objects of bodily provocation” (2004, p.79).

If the spectator is in an exchange of sensual connection with the character, to what extent does this exchange occur? Clearly I will not feel the same physical trauma of Sara Goldfarb’s electrotherapy, Max’s seizure, or Harry’s infected arm (all in Requiem for a Dream). To do so would create an untenable experience for the spectator. However, Sobchack suggests that the cinesthetic subject does at least to some extent experience the character’s physicality, due to the structure of subjective interchangeability with the character. This helps to explain why, upon seeing Harry’s infected arm I feel a discomfort in my own and am provoked to rub it. Jennifer Barker (2009, p.12) suggests that as a cinesthetic subject, I am engaged in “fleshy, muscular, visceral contact” with Harry; I feel a portion of his pain, and thus express a physical reaction to this pain by rubbing my arm.

Sobchack’s cinesthetic subject can bring about acute sensory awareness and experience. However, there are multiple factors at play. Scenes concerning Harry’s infected arm are made up of many sonic and visual components that help provoke a bodily experience in the spectator. I am not just presented with an infected looking arm, but rather I am presented with Harry’s arm through the cinematic optic of the mise-en-scène. Elements such as music, colour, and composition perform functions that operate within the visual and acoustic realm but manifest as felt experiences beyond just sight and sound. Consider the scene of Harry lying on the prison floor, writhing in agony with an infected arm (see Figure 3.1). The mise-en-scène consists of the blue and grey hues of Harry’s prison attire and the prison floor. These hues are contrasted with the warmer skin tones of Harry’s arm and face. The colour complexion enhances the spectator’s engagement with the visceral nature of this scene. The blue/grey hues command the greater portion of the screen’s real estate and therefore create a cold environment. However, the contrast between these hues with Harry’s pale pink skin highlights the infected area of his arm. This contrast brings the infection to the forefront of the spectator’s attention, highlighting the pain and allowing the spectator, through cinesthesia, to feel a portion of the same. I am mindful here of colour’s power to influence the spectator. It is worth noting that colour alone does not produce such responses, but must work in conjunction with other cinematic elements of the mise-en-scène such as sound, performance, and framing.

Sobchack’s cinesthetic subject can bring about acute sensory awareness and experience. However, there are multiple factors at play. Scenes concerning Harry’s infected arm are made up of many sonic and visual components that help provoke a bodily experience in the spectator. I am not just presented with an infected looking arm, but rather I am presented with Harry’s arm through the cinematic optic of the mise-en-scène. Elements such as music, colour, and composition perform functions that operate within the visual and acoustic realm but manifest as felt experiences beyond just sight and sound. Consider the scene of Harry lying on the prison floor, writhing in agony with an infected arm (see Figure 3.1). The mise-en-scène consists of the blue and grey hues of Harry’s prison attire and the prison floor. These hues are contrasted with the warmer skin tones of Harry’s arm and face. The colour complexion enhances the spectator’s engagement with the visceral nature of this scene. The blue/grey hues command the greater portion of the screen’s real estate and therefore create a cold environment. However, the contrast between these hues with Harry’s pale pink skin highlights the infected area of his arm. This contrast brings the infection to the forefront of the spectator’s attention, highlighting the pain and allowing the spectator, through cinesthesia, to feel a portion of the same. I am mindful here of colour’s power to influence the spectator. It is worth noting that colour alone does not produce such responses, but must work in conjunction with other cinematic elements of the mise-en-scène such as sound, performance, and framing.

I have adjusted the original still (Figure 3.1), adding browner hues (see Figure 3.2), and have found the result to exhibit a different set of qualities. The cold tonal range is greatly reduced and the scene feels warmer and less hostile. Harry’s pale skin now looks more healthy. This small colour grading adjustment illustrates how the complexion of a scene has the potential to alter spectatorial response and engagement.

I have adjusted the original still (Figure 3.1), adding browner hues (see Figure 3.2), and have found the result to exhibit a different set of qualities. The cold tonal range is greatly reduced and the scene feels warmer and less hostile. Harry’s pale skin now looks more healthy. This small colour grading adjustment illustrates how the complexion of a scene has the potential to alter spectatorial response and engagement.

In her analysis of Derek Jarman’s monochromatic film, Blue (1993), Sobchack argues for a multi-sensory experience, despite the fact that Blue contains no image other than the unchanging titular hue for the entire film. The experience of a single hue, Sobchack argues, affects the embodied spectator profoundly when one chooses to experience the film phenomenologically:

The phenomenological method ‘fleshes out’ our initial interpretations and reveals that Blue is not only objectively about the richness, complexity, and sensuality of audiovisual perception [but also] reveals that Blue is performative: through its seeming ‘minimalism’, subjectively constituting for its viewers/listeners a meaningful experience of extreme self-reflection on the dynamics, habits, creativity, and plenitude of their own embodied perception (2011, p.204).

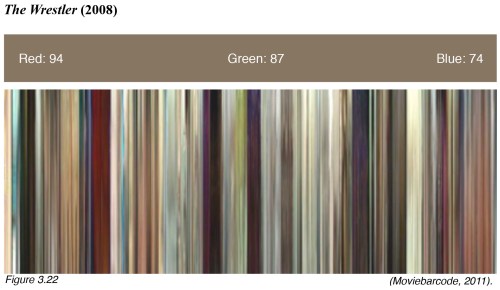

Blue may be an extreme case, and the assaultive experience of being subjected to a single colour for the entire length of a feature film is perhaps unsurprising. However, Sobchack’s approach can be extended to considering the dominant and holistic hues of standard cinematic fare, as will be demonstrated. When one considers a film’s complexion phenomenologically, it provokes a primary response, one that has no immediate cognitive assessment. Consider Aronofsky’s first five feature-length films: I am immediately aware of their chromatic complexion after a single viewing. I feel that The Wrestler is green, and The Fountain is gold, and so on. The impression that colour indelibly stamps on us as embodied spectators, encourages feeling states and leads to the onset of mood.

You can read my entire thesis on Aronofsky and phenomenology by following this link.

I am always on the look-out for a holiday film that draws out deeper reactions in my kids than a couple of cheap laughs. A few years ago, I took them to see Spike Jonze’s superb Where the Wild Things Are. Fair to say I was impressed by how complex themes were drawn out of Maurice Sendak’s seemingly innocuous 1973 book of the same name. It appeared to me that Pete’s Dragon might just have the same opportunity.

I am always on the look-out for a holiday film that draws out deeper reactions in my kids than a couple of cheap laughs. A few years ago, I took them to see Spike Jonze’s superb Where the Wild Things Are. Fair to say I was impressed by how complex themes were drawn out of Maurice Sendak’s seemingly innocuous 1973 book of the same name. It appeared to me that Pete’s Dragon might just have the same opportunity.

I have explained in a previous post the significance of cinematic colour complexion to aid our ability to “feel” a film. You can read my entire thesis on Aronofsky and phenomenology by

I have explained in a previous post the significance of cinematic colour complexion to aid our ability to “feel” a film. You can read my entire thesis on Aronofsky and phenomenology by

Sobchack’s cinesthetic subject can bring about acute sensory awareness and experience. However, there are multiple factors at play. Scenes concerning Harry’s infected arm are made up of many sonic and visual components that help provoke a bodily experience in the spectator. I am not just presented with an infected looking arm, but rather I am presented with Harry’s arm through the cinematic optic of the mise-en-scène. Elements such as music, colour, and composition perform functions that operate within the visual and acoustic realm but manifest as felt experiences beyond just sight and sound. Consider the scene of Harry lying on the prison floor, writhing in agony with an infected arm (see Figure 3.1). The mise-en-scène consists of the blue and grey hues of Harry’s prison attire and the prison floor. These hues are contrasted with the warmer skin tones of Harry’s arm and face. The colour complexion enhances the spectator’s engagement with the visceral nature of this scene. The blue/grey hues command the greater portion of the screen’s real estate and therefore create a cold environment. However, the contrast between these hues with Harry’s pale pink skin highlights the infected area of his arm. This contrast brings the infection to the forefront of the spectator’s attention, highlighting the pain and allowing the spectator, through cinesthesia, to feel a portion of the same. I am mindful here of colour’s power to influence the spectator. It is worth noting that colour alone does not produce such responses, but must work in conjunction with other cinematic elements of the mise-en-scène such as sound, performance, and framing.

Sobchack’s cinesthetic subject can bring about acute sensory awareness and experience. However, there are multiple factors at play. Scenes concerning Harry’s infected arm are made up of many sonic and visual components that help provoke a bodily experience in the spectator. I am not just presented with an infected looking arm, but rather I am presented with Harry’s arm through the cinematic optic of the mise-en-scène. Elements such as music, colour, and composition perform functions that operate within the visual and acoustic realm but manifest as felt experiences beyond just sight and sound. Consider the scene of Harry lying on the prison floor, writhing in agony with an infected arm (see Figure 3.1). The mise-en-scène consists of the blue and grey hues of Harry’s prison attire and the prison floor. These hues are contrasted with the warmer skin tones of Harry’s arm and face. The colour complexion enhances the spectator’s engagement with the visceral nature of this scene. The blue/grey hues command the greater portion of the screen’s real estate and therefore create a cold environment. However, the contrast between these hues with Harry’s pale pink skin highlights the infected area of his arm. This contrast brings the infection to the forefront of the spectator’s attention, highlighting the pain and allowing the spectator, through cinesthesia, to feel a portion of the same. I am mindful here of colour’s power to influence the spectator. It is worth noting that colour alone does not produce such responses, but must work in conjunction with other cinematic elements of the mise-en-scène such as sound, performance, and framing. I have adjusted the original still (Figure 3.1), adding browner hues (see Figure 3.2), and have found the result to exhibit a different set of qualities. The cold tonal range is greatly reduced and the scene feels warmer and less hostile. Harry’s pale skin now looks more healthy. This small colour grading adjustment illustrates how the complexion of a scene has the potential to alter spectatorial response and engagement.

I have adjusted the original still (Figure 3.1), adding browner hues (see Figure 3.2), and have found the result to exhibit a different set of qualities. The cold tonal range is greatly reduced and the scene feels warmer and less hostile. Harry’s pale skin now looks more healthy. This small colour grading adjustment illustrates how the complexion of a scene has the potential to alter spectatorial response and engagement.