Amazing Grace

Archival footage documentaries are knocking it out of the park at the moment. And if last week’s release, the technically dazzling Apollo 11, literally took you to the moon and back, then Amazing Grace metaphorically does the same with a cinematically enthralling and spiritually charged presentation of a titanic talent.

Archival footage documentaries are knocking it out of the park at the moment. And if last week’s release, the technically dazzling Apollo 11, literally took you to the moon and back, then Amazing Grace metaphorically does the same with a cinematically enthralling and spiritually charged presentation of a titanic talent.

In 1972 Aretha Franklin returned to her roots and graced the microphone laden pulpit of the New Temple Missionary Baptist Church in Los Angeles to record her iconic gospel album, Amazing Grace. Standing beneath a giant mural of Jesus Christ (looking every inch a Californian surfer-dude) and backed by the Southern California Community Choir, Franklin belts out an array of gospel songs to an enraptured congregation—the footage of which is almost an other-worldly experience to take in.

The late great director Sydney Pollack (Out of Africa, Tootsie) was tasked with the job of recording the show for later release. Unfortunately, it became an incomplete project, and while Franklin’s recorded album went on the be the biggest selling gospel album of all time, Pollack’s footage was separated from its soundtrack and lay dormant in the vaults for decades.

Thankfully, director Alan Elliott has taken the reins of Pollack’s wandering horse and lead it back to water. And drink deeply from the spiritual well this final film does. Raw and shambolic in appearance, the film’s imperfections only serve to enrich and highlight Franklin’s jaw-dropping vocals. It captures a sense of dignity and authenticity to her performance that peaks at the film’s titular centrepiece—a sweaty, focussed and transcendent rendition of Amazing Grace that is tearfully received by both the congregation and backing performers alike.

Pollack clearly looks like someone who has found the winning lottery ticket as he joyously, but frantically, gestures his crew to point their camera to this once-in-a-life-time performance and then off stage to an audience that can no longer contain themselves (Mick Jagger included). It’s impossible not to get caught up in the emotion of it all, and if this film doesn’t move you then you might want to check your pulse.

See my reviews for the NZ Herald here and for Witchdoctor here.

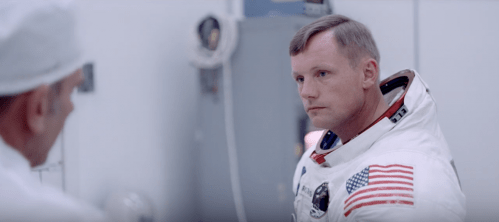

From the opening shot of workers ushering the gigantic Saturn V rocket into place like ants hauling a giant stick-insect, Apollo 11 broadsides you with absolute awe. First, at the enormity of man’s creation, and then at the realisation that the crystal clear images unfolding before you are half a century old.

From the opening shot of workers ushering the gigantic Saturn V rocket into place like ants hauling a giant stick-insect, Apollo 11 broadsides you with absolute awe. First, at the enormity of man’s creation, and then at the realisation that the crystal clear images unfolding before you are half a century old.

Breakfast Clubber, Emilio Estevez, is causing more trouble in the library, this time jumping over the counter and playing a rogue librarian rather than a rogue student.

Breakfast Clubber, Emilio Estevez, is causing more trouble in the library, this time jumping over the counter and playing a rogue librarian rather than a rogue student. Actress and activist, Olivia Wilde, has kicked off her feature directing career with a trailblazing teen comedy that belies her inexperience as a film-maker.

Actress and activist, Olivia Wilde, has kicked off her feature directing career with a trailblazing teen comedy that belies her inexperience as a film-maker. The giant acting talent of Brian Cox (Churchill) tackles the role of a cantankerous old Scotsman, Rory, who is forced from his peaty shores across the pond to seek medical treatment in San Francisco. A preference for rough-hewn edges rather than America’s modern clean lines, Rory also uses the trip to begrudgingly reconnect with his son Ian, after a fifteen-year absence. Ian is a chemist-come-chef whose Heston Blumenthal styled ultra-modern gastronomic creations wow patrons with their smokey bluster and gelatinous wonder—a far cry from Rory’s preference for black pudding and two veg. Unsurprisingly, the two don’t see eye to eye.

The giant acting talent of Brian Cox (Churchill) tackles the role of a cantankerous old Scotsman, Rory, who is forced from his peaty shores across the pond to seek medical treatment in San Francisco. A preference for rough-hewn edges rather than America’s modern clean lines, Rory also uses the trip to begrudgingly reconnect with his son Ian, after a fifteen-year absence. Ian is a chemist-come-chef whose Heston Blumenthal styled ultra-modern gastronomic creations wow patrons with their smokey bluster and gelatinous wonder—a far cry from Rory’s preference for black pudding and two veg. Unsurprisingly, the two don’t see eye to eye. The Irish poet David Whyte once penned “abandon the shoes that had brought you here right at the water’s edge, not because you had given up but because now, you would find a different way to tread”. He was referring to the Camino de Santiago, an 800km walk that finishes at the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in northwestern Spain. The long trek acts as a spiritual journey for hundreds of thousands of pilgrims a year, and while Whyte’s poem so eloquently expounds upon his niece’s journey through the fabled Spanish hinterland, this documentary focusses on people from our own back-yard.

The Irish poet David Whyte once penned “abandon the shoes that had brought you here right at the water’s edge, not because you had given up but because now, you would find a different way to tread”. He was referring to the Camino de Santiago, an 800km walk that finishes at the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in northwestern Spain. The long trek acts as a spiritual journey for hundreds of thousands of pilgrims a year, and while Whyte’s poem so eloquently expounds upon his niece’s journey through the fabled Spanish hinterland, this documentary focusses on people from our own back-yard. In his first feature, Belgian writer/director Lukas Dhont has tightly packed a cinematic masterpiece into a topical powder keg. It’s little wonder that a production about a transgender ballerina has courted so much controversy; the pitfalls of which were well documented by Dhont’s well-meaning, but perhaps naive blind-casting of its lead role, Lara. In the end, he settled on a cis male actor, Victor Polster, to play a teenage girl who was born a male, much to the chagrin of the trans-community who felt it more appropriate that Lara be played by a transgender actor at the very least. There are valid points on both sides of the ledger, and notwithstanding further controversies, it’s a wonder that this hot potato of a film ever got off the ground. I’m glad it did.

In his first feature, Belgian writer/director Lukas Dhont has tightly packed a cinematic masterpiece into a topical powder keg. It’s little wonder that a production about a transgender ballerina has courted so much controversy; the pitfalls of which were well documented by Dhont’s well-meaning, but perhaps naive blind-casting of its lead role, Lara. In the end, he settled on a cis male actor, Victor Polster, to play a teenage girl who was born a male, much to the chagrin of the trans-community who felt it more appropriate that Lara be played by a transgender actor at the very least. There are valid points on both sides of the ledger, and notwithstanding further controversies, it’s a wonder that this hot potato of a film ever got off the ground. I’m glad it did. Writer, director, star and chief financier Liam O Mochain crafts a collection of sketches about life in and around an Irish train station. Although billed as a comedy, Lost & Found is very light on laughs, rather this is more an observational film that expounds on the tall-tales you’d expect to overhear at the local pub. No surprise then, that O Mochain’s anecdotal ephemera were indeed inspired by true stories; among them are wedding proposal antics, a Publican’s opening night anguish, a treasure hunting son, funeral wakes, and of course the lost property desk clerk, David (O Mochain), around whom the film loosely centres.

Writer, director, star and chief financier Liam O Mochain crafts a collection of sketches about life in and around an Irish train station. Although billed as a comedy, Lost & Found is very light on laughs, rather this is more an observational film that expounds on the tall-tales you’d expect to overhear at the local pub. No surprise then, that O Mochain’s anecdotal ephemera were indeed inspired by true stories; among them are wedding proposal antics, a Publican’s opening night anguish, a treasure hunting son, funeral wakes, and of course the lost property desk clerk, David (O Mochain), around whom the film loosely centres. Korean director Bong Joon-ho has once again lanced the infected boil on the bum of society: inequality. Those who saw his sci-fi action-thriller Snowpiercer (which cut a strikingly violent image of a class system gone awry) will know he isn’t a stranger to the topic. While far less abrasive, Bong’s latest, this year’s Palme d’Or winning Parasite, is no less pointed. Rather, this time he gives us the same critical castigation cloaked in the tranquility of a present-day urban setting.

Korean director Bong Joon-ho has once again lanced the infected boil on the bum of society: inequality. Those who saw his sci-fi action-thriller Snowpiercer (which cut a strikingly violent image of a class system gone awry) will know he isn’t a stranger to the topic. While far less abrasive, Bong’s latest, this year’s Palme d’Or winning Parasite, is no less pointed. Rather, this time he gives us the same critical castigation cloaked in the tranquility of a present-day urban setting.